20518

Followers

29

Following

Sabbie Dare and Friends

I have been writing fiction since my reception teacher, Mrs Marsden, put a paper and pencil in front of me. I can remember thinking; What? Do real people write these lovely books? I want to do that! I gained an MA in creating writing and sold my first books for children; Sweet’n’Sour, (HarperCollins) and Tough Luck, (Thornberry Publishing), both from Amazon. I also love writing short stories and they regularly appear in British anthologies.

I now write crime fiction, published by Midnight Ink. The idea for In the Moors , my first Shaman Mystery came to me one day, in the guise of Sabbbie Dare. She came to me fully formed and said; “I'm a young therapist, a shaman, and sometimes I do get very strange people walking into my therapy room. Honestly, I could write a book about some of them...”

I am a druid; a pagan path which takes me close to the earth and into the deep recesses of my mind. Shamanic techniques help me in my life - in fact they changed my life - although, unlike Sabbie, I’ve never set up a therapeutic practice...I’m too busy writing and teaching creative writing with the Open College of the Arts. I’m a fellow of the Higher Education Academy.

Although I was born, educated and raised my two children in the West Country, I now live in west Wales with my husband James.

IN THE MOORS, the first Shaman Mystery starring SABBIE DARE was released in the US in 2013 and UNRAVELLING VISIONS will be out this autumn, but you can already reserve your copy on Amazon.

Join me on my vibrant blogsite, http://www.kitchentablewriters.blogspot.com where I offer students and other writers some hard-gained advice on how to write fiction.

MOBY-DICK; or THE WHALE by Herman Melville

MOBY-DICK; or THE WHALE

by Herman Melville

'Read Classic', an occasional series of posts on

Kitchentablewriters.blogspot.com

A friend gave me my copy of Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville as a gift, around 15 years ago. It measures 6 1⁄2” by 4” by 1 1⁄2” with 798 gold-edged wafer-thin pages and 135 chapters, a ‘Collector’s Library’ edition, ‘complete and unabridged’.

When I first tried to read it, I got bored quickly. I was 150 pages in and they’d only just gone aboard The Pequod – 200 pages in and we still hadn’t met Ahab…

Steadily, I read less, until the little golden book was forgotten.

Then my reading group, bless them, decided that we should all read a different 19th century American work. I pulled out Moby-Dick, blew off its dust and started again.

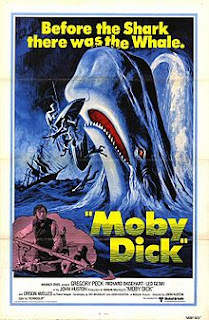

Maybe I was in a different place, a different reading mindset. But instantly, I loved it. I dove into the rich, warming narrative – words that go on and on. I swam within them as if they were fish teeming in the Pacific. I’d finished it within the four allotted weeks, and watched the 1956 film, starring Gregory Peck as Ahab, with a screenplay by Ray Bradbury. At the meeting, I read out the passages I particularly loved…

And then it was, that suddenly sweeping his sickle-shaped lower jaw beneath him, Moby Dick had reaped away Ahab's leg, as a mower a blade of grass in the field.... Small reason was there to doubt, then, that ever since that almost fatal encounter, Ahab had cherished a wild vindictiveness against the whale, all the more fell for that in his frantic morbidness he at last came to identify with him, not only all his bodily woes, but all his intellectual and spiritual exasperations.

Chapter 41, Moby Dick

|

| Herman Melville |

Herman Melville was born in New York in 1819 and by the age of 13 was working in a bank. At 18 he completed his education and moved from job to job; school teacher, newspaper reporter, merchant sailor. He went West to (unsuccessfully) seek his fortune. Down on his luck he set sail on a whaler bound for the South Seas, where he spent time in the company of the natives. He detailed his adventures in a series of novels which, in his own lifetime, proved continually more popular than Moby-Dick.

MOBY-DICK; or THE WHALE, first appeared in 1851, when he was 32. Now, it is considered his seminal work, and having read it, I know it is a masterpiece, a gothic philosophical allegory and a scathing satire on life.

It is profoundly inventive, intense and ironic, the style and language standing alongside other great experimental novels, from Tristram Shandy to Ulysses. I loved its soaring voice, which moves from long passages of soliloquy, through pieces of script format, to sharp and dramatic dialogue…

…“Look ye! d'ye see this Spanish ounce of gold?"- holding up a broad bright coin to the sun- "it is a sixteen dollar piece, men. D'ye see it? Mr. Starbuck, hand me yon top-maul."

While the mate was getting the hammer, Ahab, without speaking, was slowly rubbing the gold piece against the skirts of his jacket, as if to heighten its lustre, and without using any words was meanwhile lowly humming to himself, producing a sound so strangely muffled and inarticulate that it seemed the mechanical humming of the wheels of his vitality in him.

Receiving the top-maul from Starbuck, he advanced towards the main-mast with the hammer uplifted in one hand, exhibiting the gold with the other, and with a high raised voice exclaiming: "Whosoever of ye raises me a white-headed whale with a wrinkled brow and a crooked jaw; whosoever of ye raises me that white-headed whale, with three holes punctured in his starboard fluke- look ye, whosoever of ye raises me that same white whale, he shall have this gold ounce, my boys!"

"Huzza! huzza!" cried the seamen, as with swinging tarpaulins they hailed the act of nailing the gold to the mast.

"It's a white whale, I say," resumed Ahab, as he threw down the topmaul: "a white whale. Skin your eyes for him, men; look sharp for white water; if ye see but a bubble, sing out."

All this while Tashtego, Daggoo, and Queequeg had looked on with even more intense interest and surprise than the rest, and at the mention of the wrinkled brow and crooked jaw they had started as if each was separately touched by some specific recollection.

"Captain Ahab," said Tashtego, "that white whale must be the same that some call Moby Dick.”

Chapter 36, The Quarter-Deck.

Most of the information between the pages is now anachronistic and almost forgotten, but I was fascinated by how whale blubber was rendered down on board into barrels of oil – how the first steak from a kill would be eaten ceremoniously. And yet, counterpointing all the minutiae and trivia, the ways of Moby Dick remain unknown. Melville (and Ishmael) are sure upon that; the white whale is like God in his Heaven, which makes Ahab a fool for trying to find and outdo him. The result, of course, is futile…and fatal.

The book teems with ideas, imagery and emotion, but between these subtleties lie those hard facts. Melville makes use of his first-hand descriptions of whaling alongside an encyclopaedic knowledge of the nature of the whale…

The Forty-barrel-bull schools are larger than the harem schools. Like a mob of young collegians, they are full of fight, fun, and wickedness, tumbling round the world at such a reckless, rollicking rate, that no prudent underwriter would insure them any more than he would a riotous lad at Yale or Harvard. They soon relinquish this turbulence though, and when about three-fourths grown, break up, and separately go about in quest of settlements, that is, harems.

Another point of difference between the male and female schools is still more characteristic of the sexes. Say you strike a Forty-barrel-bull- poor devil! all his comrades quit him. But strike a member of the harem school, and her companions swim around her with every token of concern, sometimes lingering so near her and so long, as themselves to fall a prey.

Chapter 88, Schools and Schoolmasters

The book is chocked with symbolic motifs which develop and inform the text’s major themes, and I enjoyed spotting them. The first one is the colour white, which Ishmael, finds threatening; white waves albinos, whale spout…

It was while gliding through these latter waters that one serene and moonlight night, when all the waves rolled by like scrolls of silver; and, by their soft, suffusing seethings, made what seemed a silvery silence, not a solitude: on such a silent night a silvery jet was seen far in advance of the white bubbles at the bow. Lit up by the moon, it looked celestial; seemed some plumed and glittering god uprising from the sea…

Chapter 51, The Spirit-Spout

Then there is the coffin, which symbolizes life and death. When Ishmael’s friend, the harpooner Queequeg, falls ill, he asks the carpenter to build him a coffin, but survives and stores his belongings in it. When the Pequod sinks, the coffin becomes Ishmael’s lifeboat.

Call me Ishmael. Some years ago -- never mind how long precisely -- having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world. It is a way I have of driving off the spleen, and regulating the circulation. Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people's hats off -- then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball.

Chapter 1, Loomings

And the themes themselves are grand. Like the heroes of Greek or Shakespearean tragedy, Ahab suffers from a single fatal flaw. He is obsessed, monomaniacal, believing that, like a god, he will remain immune to the forces of nature while pursuing the White Whale…it’s his inescapable fate to destroy this evil.

The Pequod represents the world…its crew, all of humanity’s fears, frailties and faiths are acted out. It is a symbol of doom, painted black and covered in whale teeth and bones, mementos of their violent death. The name was taken from a Native American tribe made extinct by the white invaders.

But despite the wanderings of both book and ship, there is a plot, and it uses causality, something I love in a story. From the beginning, Ishmael notes Ahab’s eccentricity and madness getting worse, until, The Pequod encounters the whaling ship Rachel, imploring help to search for the missing whaling-crew, including the captain's son. But as soon as Ahab learns that the crew disappeared while tangling with Moby-Dick he refuses the call to aid – something unheard of in whaling tradition – and goes off to hunt the White Whale. After The Pequod goes down, Ishmael, in his coffin, is ironically rescued by the Rachel which has continued to search for its missing crew.