Sabbie Dare and Friends

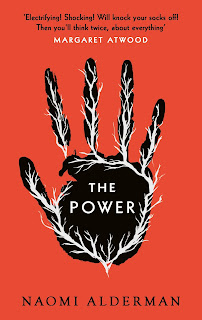

THE POWER

In Death of an Author, Roland Barthes argued that readers should ‘liberate’ their reading, from the ‘interpretive tyranny’ of the critic who first looks at the writer, their ethnicity, politics, religion, even personal attributes and relates these to the reading. For instance, if the writer was a known 30’s fascist, then that would be immediately taken into consideration to be part of gaining the meaning. The essential meaning of a work depends on the impressions of the reader, rather than the passions of the writer; a text's unity lies not in its origins, or its creator, but in its destination, or its audience.

In Death of an Author, Roland Barthes argued that readers should ‘liberate’ their reading, from the ‘interpretive tyranny’ of the critic who first looks at the writer, their ethnicity, politics, religion, even personal attributes and relates these to the reading. For instance, if the writer was a known 30’s fascist, then that would be immediately taken into consideration to be part of gaining the meaning. The essential meaning of a work depends on the impressions of the reader, rather than the passions of the writer; a text's unity lies not in its origins, or its creator, but in its destination, or its audience. |

| http://www.naomialderman.com/about/ |

If the book had been written the other way around, with men being all-powerful, we would more or lesws be reading about the real world, the one we live in. So how does Alderman visualise such a dramatic change as this? You’d think the prediction for a sudden matriarchal society would be that it’s more caring and nurturing than this one, where men are generally in charge. But the story is dystopian, suggesting that absolute power really does corrupt absolutely. Men become second-class citizens and this world unfurls into a mirror image of the one it left behind.

Readers had mixed opinions. It won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year and Granta Best of British writer. It’s getting five stars on all the review sites (mostly from women, which made me wonder if men are reading it). But when I went to my book club, all women, I was surprised to find that they all agreed with me, that this book, although a thought-provoking read, should not have won a major prize like the Bailey’s Women’s Prize. My reading friends agreed that the writing in The Power is not elevated or illuminating, that it read at the same level as something like The Hunger Games; fast-paced and easy to race through – a thriller, yes, but the language is basic and at times clumsy, and the characters are thinly revealed or developed. We didn't rate it as a work of literature. Perhaps that was mean of us. We already knew that Atwood had loved the book; did that influence us adversly? And in any case, does our opinion change what the book originally meant?

Readers had mixed opinions. It won the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year and Granta Best of British writer. It’s getting five stars on all the review sites (mostly from women, which made me wonder if men are reading it). But when I went to my book club, all women, I was surprised to find that they all agreed with me, that this book, although a thought-provoking read, should not have won a major prize like the Bailey’s Women’s Prize. My reading friends agreed that the writing in The Power is not elevated or illuminating, that it read at the same level as something like The Hunger Games; fast-paced and easy to race through – a thriller, yes, but the language is basic and at times clumsy, and the characters are thinly revealed or developed. We didn't rate it as a work of literature. Perhaps that was mean of us. We already knew that Atwood had loved the book; did that influence us adversly? And in any case, does our opinion change what the book originally meant? Finally, we asked this…was there a more worthy winner on the short list?

On the other hand, readers don’t seem to be interested in the idea that we should make up our mind only through our reading, and not from any outside inflences. The Radio 4 favourite, Book Club, wouldn’t be so loved if that were true. In this programme, you are told in advance which author will be attending with a studio audience, who will ask questions about the author’s recent work. For the same reason, Book Festivals, are massively attended. We all want to hear what the author says about their own work.

Would The Power have won the Bailey’s if the judges hadn’t known that Margaret Atwood ‘mentored’ the book and gave it her wholehearted support? Atwood is justly renown for both her early works, which gave her a ‘name’ and for her later science fiction, but mostly, she’s in the news at the moment for the brilliant TV adaptation of Handmaid’s Tale. At our book club we couldn’t understand what she saw in this book, which we agreed was original and inventive, but concentrated on pursuing the idea that girls could now inflict pain, and describing gratuitous acts of violence, death and rape. What if a man had written this self-same book? Would it have been lauded, especially by feminists? Or would they have suggested that the dystopian nature of the outcome was due to a ‘male view’? What if the athour had reversed the theme, so that it was men who were born with electrocuting ‘skeins’? Would this book, as it stands, but gender reversed, have been read as literature? Or marketed under a lurid cover?

Would The Power have won the Bailey’s if the judges hadn’t known that Margaret Atwood ‘mentored’ the book and gave it her wholehearted support? Atwood is justly renown for both her early works, which gave her a ‘name’ and for her later science fiction, but mostly, she’s in the news at the moment for the brilliant TV adaptation of Handmaid’s Tale. At our book club we couldn’t understand what she saw in this book, which we agreed was original and inventive, but concentrated on pursuing the idea that girls could now inflict pain, and describing gratuitous acts of violence, death and rape. What if a man had written this self-same book? Would it have been lauded, especially by feminists? Or would they have suggested that the dystopian nature of the outcome was due to a ‘male view’? What if the athour had reversed the theme, so that it was men who were born with electrocuting ‘skeins’? Would this book, as it stands, but gender reversed, have been read as literature? Or marketed under a lurid cover?Meanwhile, my book club had all read the rest of the shortlist, and we all preferred one particular book. It didn't win, but nevertheless it's a total winner in our opinion.

Which was was it? Well, that's what suspension is all about folks. I'll review it, as my favourite book of 2017, in my next blogpost.

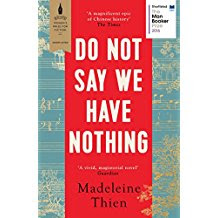

DO NOT SAY WE HAVE NOTHING

I tried again. “Ma told me it’s a great adventure, that someone goes to America and someone else goes to the desert. She said that the person who made this copy is a master calligrapher.”

I tried again. “Ma told me it’s a great adventure, that someone goes to America and someone else goes to the desert. She said that the person who made this copy is a master calligrapher.” |

| Tieananmen Square in the 80s |

1

1

Writng Advice - Questing your Plot

Questing your Plot

Writing Advice - Getting Going

A Five-finger Exercise for Writers

When I was a small child, just starting school, my favorite moment in each day was the one, after we’d finished our tea, when my father went into the front room. He’d say to me, ‘don’t pull the curtains and don’t switch on the light.’ Then he’d sit at his piano in the last of the evening light and play; Chopin waltzes, Mendelsshon’s Songs without Words, Beethoven sonatas and pieces from the shows. I would dance around the room for hours, my skirts twirling, my arms doing what I thought might be pointy ballerina movements.

When I was a small child, just starting school, my favorite moment in each day was the one, after we’d finished our tea, when my father went into the front room. He’d say to me, ‘don’t pull the curtains and don’t switch on the light.’ Then he’d sit at his piano in the last of the evening light and play; Chopin waltzes, Mendelsshon’s Songs without Words, Beethoven sonatas and pieces from the shows. I would dance around the room for hours, my skirts twirling, my arms doing what I thought might be pointy ballerina movements.  Spot on, Bill. Writing a novel is like inventing an entire new life...many people’s lives, actually. If you’re into fantasy, you’ll be inventing new worlds, as well. How could that possibly be easy? Certainly, having a mentor who can support you in those first stages when it all seems a complete mess - when even the five-finger exercises of writing feel onerous - can help enormously. Bill wrote; When you are placed with a tutor there is initially, a certain amount of natural apprehension. You’re faced with another lengthy and unknown learning process. My initial feeling was that the way ahead seemed insurmountable. I’d spent a few months standing still and had reached a non-constructive plateau without any end in sight. It felt I was drowning in a sea of uncertainty. You reassured me that I was not alone with this problem and that most novice or indeed many professional writers suffered this at one time or another during their writing career. The way through this dilemma and off the plateau was to keep on writing.

Spot on, Bill. Writing a novel is like inventing an entire new life...many people’s lives, actually. If you’re into fantasy, you’ll be inventing new worlds, as well. How could that possibly be easy? Certainly, having a mentor who can support you in those first stages when it all seems a complete mess - when even the five-finger exercises of writing feel onerous - can help enormously. Bill wrote; When you are placed with a tutor there is initially, a certain amount of natural apprehension. You’re faced with another lengthy and unknown learning process. My initial feeling was that the way ahead seemed insurmountable. I’d spent a few months standing still and had reached a non-constructive plateau without any end in sight. It felt I was drowning in a sea of uncertainty. You reassured me that I was not alone with this problem and that most novice or indeed many professional writers suffered this at one time or another during their writing career. The way through this dilemma and off the plateau was to keep on writing. I'm lucky enough to have a wonderful set of mentors; the literary agency I'm with. They don't just turn my work around, and send it off to editors with a hopeful covering letter, they constantly work with me to get my novels to a perfect pitch. Like Bill, I'm no better at seeing the trees in my own writing…I fancy almost all professional writers find it hard to find a navigable path through the thickest parts of their novel's woodland – at least during the first drafts. Maybe this is the reason many second novels get slated by critics and readers alike; 'just not like the first, great book', they'll cry, and I'll be thinking, 'didn't their agent read it over and comment on it, offer some advice?' That's when I know I'm so lucky to have great agents.

One thing I can reassure him on – and all the writers who are in his position that read this blog – it does, slowly, get easier. Tiny step by tiny step, you start to work things out on your own, spotting what's wrong in time to get it right, learning to take that step back and look at the forest, see how it's growing.

To learn more about my mentoring programme, go to KITCHEN TABLE NOTEPAD PROGRAMME

To learn more about my mentoring programme, go to KITCHEN TABLE NOTEPAD PROGRAMMEWriting Advice - Info Dumps

Clear Up Your Writing Info Dumps

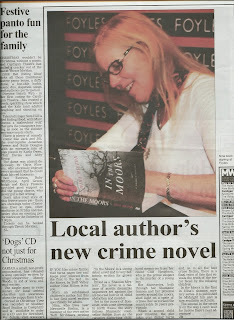

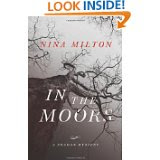

In her latest post for the Open College of the Arts, Nina Milton is writing on the information dump, a phrase used colloquially by scriptwriters, but it’s also something that can be an issue for writers of novels and short stories.

Get all Moody with your Crime Writing

The Pathetic Fallacy can entice the reader right into the mood of the narrator or other characters. Used sparingly by the skilled writer, the Pathetic Fallacy can be very effective. This term relates to the technique of attributing human characteristics, sensations, and emotions, to things that are inanimate, such as nature. The weather is used a lot within this technique. It can link extremely well with the symbolism you might want to pull into a story. For instance, when a writer wants to build up an emotion in their character, they will place them in an appropriate setting – the angry character standing below a lowering sky with bruised clouds tearing above them, or the despairing character battling against a desperate, lashing storm. Rain is always falling at funerals – lightening slashes a tree as a gothic horror begins – fog descends as the protagonist becomes wandering and confused, as in King Lear, or lost in a long, fruitless quest, as in Bleak House. But this is a device that is notoriously cliched and often wrongly applied by novice writers, leading to something called 'empathic universe', which creates a melodramatic effect. You can tell if someone has overdone their melodrama, the mood overpowers the characters and even the story, getting in the way of allowing the reader to empathize with the protagonist. Be particularly warned if you are writing romantic fiction – remind yourself of the comic effect in Wallace and Gromit as Wallace’s bread was shown rinsing in his oven as his passion bloomed for Piella Backwell. If you use this technique to make people laugh, just be sure they are laughing with you and not at your writing.

The Pathetic Fallacy can entice the reader right into the mood of the narrator or other characters. Used sparingly by the skilled writer, the Pathetic Fallacy can be very effective. This term relates to the technique of attributing human characteristics, sensations, and emotions, to things that are inanimate, such as nature. The weather is used a lot within this technique. It can link extremely well with the symbolism you might want to pull into a story. For instance, when a writer wants to build up an emotion in their character, they will place them in an appropriate setting – the angry character standing below a lowering sky with bruised clouds tearing above them, or the despairing character battling against a desperate, lashing storm. Rain is always falling at funerals – lightening slashes a tree as a gothic horror begins – fog descends as the protagonist becomes wandering and confused, as in King Lear, or lost in a long, fruitless quest, as in Bleak House. But this is a device that is notoriously cliched and often wrongly applied by novice writers, leading to something called 'empathic universe', which creates a melodramatic effect. You can tell if someone has overdone their melodrama, the mood overpowers the characters and even the story, getting in the way of allowing the reader to empathize with the protagonist. Be particularly warned if you are writing romantic fiction – remind yourself of the comic effect in Wallace and Gromit as Wallace’s bread was shown rinsing in his oven as his passion bloomed for Piella Backwell. If you use this technique to make people laugh, just be sure they are laughing with you and not at your writing. I haven't forgotten the sense of sight – describing how things appear is essential, even it if is over-used. New writers often believe 'describing' is something you really shouldn't do too much if you want to move your story on, and, indeed, today’s readers are not keen on long chunks of description…that died out with the crinoline! So the way to add atmospheric detail, especially in crime writing, is to slide it in surreptitiously as the action, interior monologue and dialogue continues to move the story on. Opening out the possiblilities by painting the atmosphere until it drips with meaning is quite the opposite of providing chunks of description.

So this is the strange truth…the more detail you chose to include, the less boring the writing becomes…moving into close-up is absorbing and paints the imagery of the story.

So this is the strange truth…the more detail you chose to include, the less boring the writing becomes…moving into close-up is absorbing and paints the imagery of the story. In this fuller version, I slowed the action by writing into the gaps

which I left out in my rush to get the first words onto the page. I added hints of the sounds that are around her, and of the smell of the moors, with words such as murky, slimy and oily. Touch sensations work exceedingly well to draw a reader into an image, for instance, how Sabbie is effected by the freezing conditions. I tried to be unpredictable, especially in my choice of and simile. I allowed the falling darkness to imprint its mood on her emotions. I ‘seeded in’ description by using symbolic imagery which might add to the mood. Rather than abstract nouns such as ‘Sabbie was scared’ I used 'show'...A gurgle of panic...My eyes stung with tears... And I've tried to draw out the experience by making things harder for Sabbie, placing obstacles in her way and allowing the loss of her torch into the bog to feel like the very last straw.

Your first draft is going to be rushed (and possibly messy) – you are trying to get down your thoughts. You might need to go back later to include atmosphere and mood. When you do, you’ll find these will also enhance your ‘writer’s voice’, and help you further understand what is behind your story.

On the Road by Cormac McCarthy

In one flashback we see the wife decide to leave them while they sleep, and go off to her death, her suicide. I found that particularly shocking, and wondered if a woman writer would have imagined this in the same way; women rarely leave their children voluntarily. So I have to think of this as a writer’s device; McCarthy wanted The Road to be about a boy and a man. I don’t blame him. What he created was powerful reading which, for all its masculine tone, is moving and full of tender love. He gets right into the head of The Man for most of the time. We never see The Boy’s thoughts, but often McCarthy moves out of the thoughts and immediate perceptions of The Man while constantly shifting from The Man's warm-hearted love to an more objective viewpoint to observe the savage, dreadful landscape and its inhabitants.

In one flashback we see the wife decide to leave them while they sleep, and go off to her death, her suicide. I found that particularly shocking, and wondered if a woman writer would have imagined this in the same way; women rarely leave their children voluntarily. So I have to think of this as a writer’s device; McCarthy wanted The Road to be about a boy and a man. I don’t blame him. What he created was powerful reading which, for all its masculine tone, is moving and full of tender love. He gets right into the head of The Man for most of the time. We never see The Boy’s thoughts, but often McCarthy moves out of the thoughts and immediate perceptions of The Man while constantly shifting from The Man's warm-hearted love to an more objective viewpoint to observe the savage, dreadful landscape and its inhabitants. You have to carry the fire.

I don't know how to.

Yes you do.

Is it real? The fire?

Yes, it is.

Where is it? I don't know where it is.

Yes you do. It's inside you. It was always there. I can see it.

McCarthy refuses to let you look away, but at the same time, you’re allowed to, sort of, because the reader is likely to identify deeply with The Boy. Like fire, he is a symbol of hope, and The Man, perpetually tender towards his son, is always making him look away from the grossness of their world, to lie in a ditch, stay out of sight. Their relationship stabilises and motivates the father. Of course it does; The Boy is all The Man has to live for and move forward for. The Boy often uses the word ‘okay’ as if to console, reassure. An understanding, came right as I began to read that first time. The Boy has learnt quickly. He does not run out of sight, he does not play unless something is initiated by his father. He does not laugh. He is rarely ‘naughty’, but occasionally, he can be cruel to his dad. He has grown old, while still small, and with it, he’s gained amazing wisdom. He’s been born into the post-apocalyptic world and has known nothing but cold, pain, ill health and fear, and yet he’s actually the one that has compassion for outsiders. I found that convincing. Children can be wonderfully ‘self-righteous’, but this compassion seems more than this, as if, with no play and no fun in his life, he’s worked through a philosophy in which kindness is paramount. After all, it’s what he has constantly received from his father, for whom he is a…golden chalice, good house to a god… Hisconstant approach becomes another rich symbol in the book. I began to see The Man as representing the human – the brutal, if sentient, creature with a strong instinct to survive. He keeps going because he must. To do what his wife did is unthinkable, even though he knows there might be a time, if they fell into the hands of a bloodcult, that death would be preferable. But to survive, they cannot show compassion to any outsider. They cannot offer food to the starving, for they are starving too. They cannot stop to help the trapped, or the distressed, because they have no time to waste, and in any case, all others are seen as a threat – best they stay trapped.

McCarthy refuses to let you look away, but at the same time, you’re allowed to, sort of, because the reader is likely to identify deeply with The Boy. Like fire, he is a symbol of hope, and The Man, perpetually tender towards his son, is always making him look away from the grossness of their world, to lie in a ditch, stay out of sight. Their relationship stabilises and motivates the father. Of course it does; The Boy is all The Man has to live for and move forward for. The Boy often uses the word ‘okay’ as if to console, reassure. An understanding, came right as I began to read that first time. The Boy has learnt quickly. He does not run out of sight, he does not play unless something is initiated by his father. He does not laugh. He is rarely ‘naughty’, but occasionally, he can be cruel to his dad. He has grown old, while still small, and with it, he’s gained amazing wisdom. He’s been born into the post-apocalyptic world and has known nothing but cold, pain, ill health and fear, and yet he’s actually the one that has compassion for outsiders. I found that convincing. Children can be wonderfully ‘self-righteous’, but this compassion seems more than this, as if, with no play and no fun in his life, he’s worked through a philosophy in which kindness is paramount. After all, it’s what he has constantly received from his father, for whom he is a…golden chalice, good house to a god… Hisconstant approach becomes another rich symbol in the book. I began to see The Man as representing the human – the brutal, if sentient, creature with a strong instinct to survive. He keeps going because he must. To do what his wife did is unthinkable, even though he knows there might be a time, if they fell into the hands of a bloodcult, that death would be preferable. But to survive, they cannot show compassion to any outsider. They cannot offer food to the starving, for they are starving too. They cannot stop to help the trapped, or the distressed, because they have no time to waste, and in any case, all others are seen as a threat – best they stay trapped. Cant we help him? Papa?

No. We cant help him.

The boy kept pulling at his coat. Papa? he said.

Stop it.

Cant we help him Papa?

No. We cant help him. There's nothing to be done for him.

McCarthy is a renowned recluse, and would never write a happy(ish) end just because he thought his readership might like it, or because his editor demanded it. I think at the end, what we see is the body stripped away, and the soul walk out of it. The boy walks into the light, taking the inner fire. As if to prove it, McCarthy finishes the book like this…

1

1

Off the Peg; how Ottessa Moshfegh wrote Eileen

If you’ve been thinking of dashing off a thriller in the hope of great success in the book market, then I would have been the first person to stop you. “Never jump on a bandwagon”, I’d have said, along with, “ignore books like Alan Watt’s The 90-Day Novel. You can’t ‘dash off’ great writing. But Ottessa Moshfegh ignored such sane suggestions and went right ahead and wrote Aileen, one of the best Mann-Booker short-listed novels I’ve read in a long time.

If you’ve been thinking of dashing off a thriller in the hope of great success in the book market, then I would have been the first person to stop you. “Never jump on a bandwagon”, I’d have said, along with, “ignore books like Alan Watt’s The 90-Day Novel. You can’t ‘dash off’ great writing. But Ottessa Moshfegh ignored such sane suggestions and went right ahead and wrote Aileen, one of the best Mann-Booker short-listed novels I’ve read in a long time.  |

| http://themanbookerprize.com/books/eileen-by-ottessa-moshfegh |

Moshfegh knows precisely what an unlikable character she’s created. In Vice Magazine she said; “My writing lets people scrape up against their own depravity, but at the same time it’s very refined … It’s like seeing Kate Moss take a shit.” To a degree she seems to be writing from experience; in the past she’s had both drink and eating problems.

And honest character who has committed the most awful crime, that is...

1

1

Dracula by Bram Stoker

Bram Stoker's Dracula

Bram Stoker's Dracula

We did a lot of walking that holiday, passing the whaling arch on West Cliff, which Stoker would have passed too, with his family, when he holidayed here in June 1990. He stayed at Royal Crescent and it was there I discovered just how inspiring his time in Whitby must have been. Bram Stoker had found his inspiration. Standing in the crescent, you have a view of the North Sea, past sloping green cliff and grey sands. Across the river estuary are the imposing ruins of the Abbey, which must have been at least as gothic then as it is now. The churchyard of St Mary lies below, the location of a vampiric attack in the second half of the story. As twilight falls, bats begin to swoop into view.

We did a lot of walking that holiday, passing the whaling arch on West Cliff, which Stoker would have passed too, with his family, when he holidayed here in June 1990. He stayed at Royal Crescent and it was there I discovered just how inspiring his time in Whitby must have been. Bram Stoker had found his inspiration. Standing in the crescent, you have a view of the North Sea, past sloping green cliff and grey sands. Across the river estuary are the imposing ruins of the Abbey, which must have been at least as gothic then as it is now. The churchyard of St Mary lies below, the location of a vampiric attack in the second half of the story. As twilight falls, bats begin to swoop into view. Bram Stoker also spent time at Whitby library – he made notes from 'An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia’, in which he must have seen the name ‘Dracula’ for the first time. The fifteenth-century Vlad Dracula (Vlad the Impaler) was as bloodthirsty as his fictional counterpart, impaling his enemies on long spikes and nailing turbans to the scalps of foreign ambassadors. Stoker gives his reader the historical allusion that Count Dracula is the descendant of Vlad – in his Author’s Note he explains that the documents assembled in the novel are real. Even as I read this, before starting the novel, I was reminded of the hype around The Blair Witch Project, and saw how astute Stoker was as a writer.

Bram Stoker also spent time at Whitby library – he made notes from 'An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia’, in which he must have seen the name ‘Dracula’ for the first time. The fifteenth-century Vlad Dracula (Vlad the Impaler) was as bloodthirsty as his fictional counterpart, impaling his enemies on long spikes and nailing turbans to the scalps of foreign ambassadors. Stoker gives his reader the historical allusion that Count Dracula is the descendant of Vlad – in his Author’s Note he explains that the documents assembled in the novel are real. Even as I read this, before starting the novel, I was reminded of the hype around The Blair Witch Project, and saw how astute Stoker was as a writer.  Stoker's masterpiece was part of a fin-de-siècle literary culture obsessed with crime – this was the time that Jack the Ripper stalked Whitechapel – and sensationalism – these were the original ‘naughties’. The book strips away the layers of late Victorian anxiety such as loss of religious traditions, colonialism, scientific advancement, plus a growing awareness of female sexuality and a continued fear of homosexuality. The book is a mirror in which generations of readers have explored their own fantasies.

Stoker's masterpiece was part of a fin-de-siècle literary culture obsessed with crime – this was the time that Jack the Ripper stalked Whitechapel – and sensationalism – these were the original ‘naughties’. The book strips away the layers of late Victorian anxiety such as loss of religious traditions, colonialism, scientific advancement, plus a growing awareness of female sexuality and a continued fear of homosexuality. The book is a mirror in which generations of readers have explored their own fantasies. In fact the main issue for me was reaching the end of the book and wondering what I could read next that would match up to it. Fortunately there is a book two and three in the series (although I started the series by reading book three, so also can confirm you can read them in any order). And hopefully Milton will continue the series with a book four.

Very addictive and highly recommended!

"

Read the latest review of NIna Milton's thriller, In the Moors, the first in the Shaman Mystery Series here; http://shamanismbooks.co.uk/in-the-moors/

2

2

Writing Advice - Making a Drama of it

One of the most useful techniques writer can stuff under their belt is the ability to control tension and create drama in their story – regardless of whether it is a piece of micro-fiction or the length of Moby Dick (whale or book). The challenges are subtly different – in a novel it’s keeping the tension going sufficiently to entice the reader the less dramatic chapters, whilst in short stories, creating a balance between the peaks and the necessary lulls in a tight space can be a test of skill.

Some apprentice writers have trouble isolating the drama in their work and often miss all the tricks in cranking up tension. They assume that events in a story will come across as dramatic – a mugging, for instance, that’s got to be drama, right? But it is so easy to muffle the tension instead of enhance it. In my children’s novel for 9+ readers, Tough Luck, I had to write a mugging scene. Here is a first draft extract; the ‘freewrite’ I scribbled down while the scene had newly come into my mind…

They were gaining on me. Each time I reached a corner, their footsteps were louder. I ran into a courtyard, hoping to lose them by twisting and turning. Instantly, I realized that I'd blown it. I was in a parking area at the back of some shops. There was only one way in - and out.

They stopped abruptly when they saw me, trapped and defeated. They began to spread out so that I had no chance of scooting around them. I stepped backwards as they moved in slowly. Then I realized I was doing what they wanted, I was backing into a wall. There'd be a moment when I could go no further, when they might pounce.

I gave it one last shot. I sprang forwards, taking them by surprise, head down, holding my skates in front of me like weapons, hurling myself between two of them. I felt hands reach out to grab me, snatch a bit of my sleeve, then one of them leapt at me, wrapping his arms round my legs in a rugby tackle. I put out my hands as the wet, glinting cobbles came up to meet me, but my nose and chin seemed to take most of the impact. The hot pain that comes when you lose a lot of skin swept over my face.

They were surrounding me. I closed my eyes as the first kick came, pulling my knees and folding my arms round my head. This was it, I thought. The very last of my bad luck. The very end of it.

A boot dug sharp into the back of my head…

As muggings go, this one is pretty mundane at the moment, but there is so much I can now do to heighten the tension and turn this into an extreme dramatic experience for character and reader alike.

Control your Reader

Some stories prefer to jog along at a steady pace until ‘bang!’ the tension is loosed like a cannon shot – often towards the end. Other stories build up tension slowly and steadily from the beginning, like tightening the elastic band on one of those little plastic aeroplanes. To help you understand how your drama functions, think about the affect you want to have on your reader. In fact focus right in on your reader’s stomach. When we read edgy, dramatic pages, our stomach knots up alongside the characters’. At first it might just be a butterfly flutter of worry. But as the tension takes hold, we begin to grip the cover tight and pant with anxiety. The writer achieves this affect by controlling what happens in the reader’s mind (and in his steadily knotting stomach) moment by moment within the narrative.

Once you have a first draft – at least in your own head or scribbled onto a plot outline –looking at how the way you tell the story will directly affect the knots in the reader’s stomach. This might mean presenting the ‘threat/mystery’ earlier in the story. Equally, it might mean holding off on the true mystery, while mini ‘subplot’ threats are seeded in.

The excerpt above is an early scene in the book – it sets the plot moving. So it should present an ‘explosion’ near the beginning that can set the blood racing and encourage the reader to then move through the next chapters - ones that burn slowly in comparison. I should let that explosion really rip. I might need to re-jig the sequence of events a bit and I should be careful not to race through it. I need to let the character (Brandon) tell his story at his own pace.

Get inside a head

Scenes should be described from inside the mind of the character most affected by any rise in tension and drama. If this isn’t possible – because your 1st person protagonist is watching the event, for instance – you must be sure that they are intensely affected by what they see – that they are able to empathize with the affected person. (Unless, of course, what you want to demonstrate is that your protagonist isn’t good at empathy, or doesn’t consider this a drama at all. If that is the case, the scene won’t be represented to the reader as drama – so be sure this is what you intended.)

Show, don’t tell will kick-start the process. Allow the character to register any physical reactions to the growth of tension inside him…my fists tightened…my heart was thumping against my ribs…my breath was coming in short, painful rasps…

Take all the time you need to make sure the reader is absolutely ‘there’ with the character(s). Don’t race through the action, or fail to report a single word spoken. Stop and use descriptive affects, ‘teasing’ your reader as unbearably as you can. Use strong verbs wherever possible to build tension. Avoid too many adjectives, but don’t avoid description…My fists tightened around the blades of my skates. They were cutting into my palms…My heart was thumping against my ribs but I couldn’t tear my eyes from the gang as my breath came in short painful rasps

Slowing Down

‘Take your time’ is one of my favourite phrases. I offer this advice to almost all my students, and so I guess I should take it myself. In the excerpt, I pummel along, looking neither to the left nor to the right. Brandon would be doing that, after all. I can’t stop the action – it is full pelt. But there are ways of holding it up while not actually stopping it. The simplest is to move into a short internal monologue. This is a renowned way of putting on the brakes at tense moments (some writers take terrible advantage of this, holding off their readers for pages, but that’s quite a risk). I must take as much time as I dare to express Brandon’s thoughts as he confronts the gang …They were gaining on me. Each time I reached a corner, their footsteps were louder – footsteps that rang on cobbled stones. I remember thinking, they're not wearing trainers.

I saw a turning ahead and swerved into it, hoping to lose them by twisting and turning. Instantly, I saw I'd blown it. I was in a parking area at the back of some shops. These were shops I'd been into, buying chocolate and chewing gum, millions of times. But now I was on the wrong side of them. There were no open doors and racks of sweeties. Just bricked up back walls…

You can see that I’m slowing the action down…writing into the gaps I left in my rush to get the words onto the page. Doing this increases tension. You wouldn’t think that would be so, but it is. The reader longs to be teased. They want to know the end of the story, the solution to the mystery, but when they reach the end they’re saddened. They wanted it to go on for ever. Otherwise Spielberg could have just spliced the first and last scenes in Jaws together and save everyone a whole evening’s viewing, or Bronte could have inscribed …reader, I married him…on the first page of Jane Eyre.

Make it Hard

Slowing down and holding back action works well to tighten the knots in the reader’s stomach. An equally good way is to make the action as difficult as possible. Make achieving a goal, even a small one, as hard as you convincingly can. Let terrible events draw out for as long as you dare, too…A boot dug sharp into the back of my head. There was a cry – I didn’t know if it was them or me. I tried to wriggle away. I felt a dead weight on my back. One of them had sat on me. The boot came again. My eyes filled with blood…

Atmosphere and Mood

These often ‘grab’ a reader and draw them in, making them feel as if they are ‘inside the story’, experiencing it physically. There is a subtle difference between these two terms:

• Atmosphere intrigues, excites, disturbs, beguiles…in other words it’s that ‘je ne sais quoi. It is often created from the setting…PJ James is good at this…or the dialogue…consider Raymond Chandler…or character description…think Dickens. To create atmosphere, let the ‘surroundings’ of each scene speak to the reader…. Just bricked up walls looming over me, black in the dark courtyard. Suddenly a security light flashed on, like we were on stage, caught in the spotlight.

• Mood is subtly different from atmosphere. It works like a perfume, subtly sensed as it further lifts the pace and atmosphere. It is usually dictated by the feelings of the protagonist or narrator... They began to spread out so that I had no chance of scooting around them. They whistled high, tuneless notes, like birds arguing over a worm. They were grinning. Their teeth glinted in the security light. They were grinning and whistling over a worm…..

The mood affects the pace, and the opposite can also be true. Atmosphere can match, shadow or underline the character’s moods. The Pathetic Fallacy can aid this, from time to time, using landscape, place/objects, climate/weather, events, etc. Truly absorbing, readable stories have braided all the effects in perfect measure.

Light and Shade…Adding Pace

It’s good for ‘light and shade’ to be added to writing. We do this even when talking, changing the tone, speed and timbre of our voice for effect. Pace…the ‘speed of the read’…is the best way to vary light with shade, and useful at encouraging dramatic tension to fluctuate in a narrative.

Pace should change regularly within a piece of writing. Of course, it’s fine to have a ‘favourite pace’ that you’ll use for the majority of the time. Particular paces attract particular readers. For instance, someone who loves the pace of a Virginia Wolfe novel, probably won’t like the pace of a Grisham, and vice versa. Pace can crawl, crush, accelerate, thrust or hurtle. We usually expect pace to be created from the action, but dialogue and even inner monologue can have pace, too. It’s used to advance the action, but can be cleverly used to delay the action – the ‘build-up’, which is often the place where the most tension lies. The pace you take your narrative at will depend on your readership, but don’t miss out on increasing the tension by varying pace at the important moments.

There are various technical ways to engender pace and so control the tension that arises, including some quite small, but important adjustments:

1a. To slow pace, use the present participle frequently.

1b. To speed it up, take them out (look for ‘ing’ endings)

2a. To slow pace, use longer words, longer speeches, words with a a smoother feel, longer sentences and longer paragraphs.

2b. To speed it up, use short, staccato words, lots of full stops and short paragraphs, snappy dialogue. Alliteration works well. Find a rhythm within the abruptness.

3a. To slow pace, use a little of the perfect tense (he had seen her) within the simple past. The passive form, although generally unwise, will slow pace. Abstract words slow pace because the reader has to ‘interpret’ them. Avoid unnecessary words such as seemed, then, also, quite, very, however, might.

3b. To speed it up, use the present tense, if possible within the context, and avoid the perfect tense, the passive form and abstract words.

4a. Look at presentation of images. To slow, give them a dreamy mood. Use all the techniques in ‘slowing down’, above.

4b. To speed up make images clear and precise, sharp sights & sounds. Don’t over describe, but metaphors and symbols can work as ‘shorthand description – sneak description into the action. Avoid adverbs like the plague. Avoid clichés, too!

In places, I need to speed my pace up. Here are the ways I utilized the ‘B’s above:

1. They howled into the courtyard…I hurled myself between two of them…

2. One last shot. I sprang forwards. My head was down. My skates were like weapons…

3. I took a step backwards. They paced forward. I stopped. I must not do what they wanted. I must not reach the wall. Once my back was against it, I was trapped.

4. The gang surrounded me. I was a worm. I was going to be squashed. Their boots scrape on the stones.

Once you have your reader’s stomach wound into a knot, it’s difficult to keep that buzz of attention when you know you need to drop the pace again. Try creating a break where the reader can take a breath – ending a scene or chapter on a ‘high’ is an accepted and common method of curtailing high tension moments. Just don’t do this until you’ve extracted every gram of possible stomach-knotting!

Flashbacks work very well at this point in a story, because they put everything completely on ‘hold’ and the reader understands that mechanism (that ‘trick’) and goes with it, taking the ‘mystery’ forward with them in the hope it will later be solved.

Interior monologue has a similar affect. Allow your character to ponder the dramatic moments or allow him to cogitate on a separate but vital issue.

Often, the moment is so dramatic that it needs to be resolved at once. I can’t leave Brandon lying helpless on the ground. Not in chapter three. I need to find a way of saving him so that he can live to tell us the rest of his story.

I’m a bit happier with this section now. It’s tighter and faster, but has variations in pace. I think I feel confident to show you the outcome…

They were gaining on me. Each time I reached a corner, their footsteps were louder – footsteps that rang on cobbled stones. They were not wearing trainers.

I saw a turning ahead and swerved into it, hoping to lose them with twists and turns. Instantly, I saw I'd blown it. I was at the back of some shops. These were shops I'd been into, buying chocolate and chewing gum, millions of times. But now I was on the wrong side of them. There were no open doors and racks of sweeties. Just bricked up walls looming over me, black in the dark courtyard as the gang from the ice rink howled in and stopped abruptly.

I took a step backwards. They paced forward. I stopped. I must not do what they wanted. I must not reach the wall. Once my back was up against it, I was trapped.

They would pounce.

My fists tightened around the blades of my skates. They were cutting into my palms. My heart was thumping against my ribs and my breath came in short painful rasps, but I couldn’t tear my eyes from the gang..

I thought about scooting round them. No chance. They spread out across the courtyard, like they were playing rugby. Suddenly a security light flashed and we were on stage, caught in the spotlight. They didn’t care. They whistled high, tuneless notes, like birds arguing over a worm. They were grinning. Their teeth glinted in the beam of light. They were grinning and whistling over a worm.

They were well spread out. I could get between them. I sprang forwards, head down. My skates were like weapons. I hurled myself between two of them. I felt hands reach out to grab me, snatch a bit of my sleeve, hang on, lose it as I kept running. For a wonderful second, I was free.

One of them leapt at me from behind, wrapping his arms round my legs in a rugby tackle. I put out my hands. The cobbles came up to meet me. The hot pain that comes when you lose a lot of skin swept over my face.

The gang was all round me. I was a worm. I was going to be squashed. Their boots scrape on the stones. I closed my eyes as the first kick came, pulled my knees up as high and folded my arms round my head. This was it, I thought. The last of my bad luck. The very end of it.

A boot dug sharp into the back of my head. There was a cry – I didn’t know if it was them or me. I tried to wriggle away. There was a dead weight on my back. One of them had sat on me. The boot came again. My eyes filled with blood. Least, that's what I thought the redness was. Then I heard the sound of an engine through the fuzz. Smelt the exhaust. A car was rolling into the courtyard.

Okay, you can unknot your stomach now…

1

1

Amahl and the Night Visitors – a storytelling experience

|

Add

caption |

Alongside my hubby, Jim, I love storytelling, and everything surrounding it… myths and folktales, personal stories, history versus legend, and the idea that, in this age of digital devices, we can still sit, spellbound, when someone opens their mouth and tells a story.

It’s surprising how easy it is in the UK to find storytelling sessions. The very best tour the country, just like rock stars, and we’ll drive a long way, and wade through a lot of mud to be at festivals, such as Beyond the Border, where performers like Daniel Morden, Hugh Lupton, Jan Blake, Eric Madden, Cath Little, and the great Robin Williamson, bewitch us with their tales.

We’ve started to include storytelling in the parties we hold; what better excuse to sit around a firepit or hearth with friends!

So, to get better acquainted with the techniques of storytelling, we joined a weekly workshop run by a professional storyteller. It was an experience – and a challenge. Each Monday, we delved into storytelling in a variety of ways, but we always started up on our feet, working on our breathing and posture, stretching, and moving to sound, singing and chanting to work our voices. When we eventually sat down, we closed our eyes and used visualization to increase what we saw in our mind’s eye.

We worked in small groups, which was interesting at first, as we didn’t know each other. Then we began to get fond of one another, and the groups became a relaxed sharing of ideas. One week, we each brought a small item that meant a lot to us. We paired off and told its history to our classmate, making notes, because it was our partner’s item we had to use to make a story we could tell to the class. These became fascinating stories, some of them closely representing the original experience, some going off on a fantastical route. We use this sort of ‘exchange’ a lot – not just using artifacts, but also recalling anecdotes in an effort to ‘release’ stories and allow us to feel we have carte blanche over them.

In another class, we learnt about the monomyth…the hero’s journey…and worked together to create our hero and discover why they journeyed from their home to a threatening, unknown place. We worked on landscape, using all sorts of settings to either create new stories or emphasize parts of familiar tales, and learned how to face an audience, how to pace stories, time the telling, and breaking it into sections and working on relating some parts faster or slower than others.

We learned that in storytelling the five senses count for the most; listeners can feel the emotions of the story via experiencing tastes and smells, textures, pain and pleasure and the entire tapestry of sounds as well as describing colours and other visual descriptions. My writing friends will know that I think the five senses are very important in writing fiction, as well, but here they became crucial to help the listener ‘see’ the story.

We also worked on detail another aspect of written stories that, as my students know, I’m always banging on about. Detail in written fiction is the lifeblood of enrichment; in storytelling it has a similar, equally essential quality of slowing the fast pace of a story and engrossing the audience.

|

Add caption |

One thing I really enjoyed as a writer, were the ‘storytelling packs’, which contained random aspects of building a story, such as character names, settings and places, times and dates, and the random symbols often found in tales, such as talking birds and fantastical beasts, deep wells and ladders of maiden's hair, magic swords and foundling babies. I found it amazing, as someone who spends a fair amount of time trying to build plots, just how simple this exercise was, and how easily a story fell into place.

As a writer of short stories, it occurs to me that the storyteller has an advantage over the writer in one important direction; they can gauge the reaction of their audience immediately. They can also employ the benefits of body language, gesture, voice control and can even add atmosphere via sound and light effects. Meanwhile, the writer put out their stories without really knowing what their readership will think of them, and without any further props to help them get their point across. Getting direct feedback from an audience is hugely scary, but the responses the storyteller wants are very similar to the ones a writer is looking for.

As we started to have the confidence to recreate and then tell stories, we were shown how to use ‘sparklines’, a method of mapping our presentation, and other ways to be able to remember where we were in our story. We began to include sound effects, background music, costumes, masks and props to aid our storytelling – better to get the basics under one’s belt before including such things – too much going on, and the novice storyteller will crash and burn!

The storyteller connects with their audience by evoking emotions from them. And the audience arrives, hoping for that; they’ve chosen the story…or the teller…because they like comic stories or sad stories or spine-chilling tales. But the storyteller will know immediately if they’ve been effective....if the audience doesn’t laugh at the funny bits, or be seen fumbling for tissues during the sad bits or gripping their knees from fear as the tension mounts, the storyteller knows right away that they have failed.

On the other hand, if feet stop shuffling, sweet wrappers stop being crackled and every eye is on the storyteller…that’s success. The story has woven its spell and the listeners are entirely absorbed. Even their breathing slows.

For the writer, too, engaging a reader from the get-go is so important. Building tension into the reading experience that holds the reader and forces them to turn the page is equally about the five senses, detail, setting, character identification and empathy. Because we’re concerned for the welfare of the protagonist – plucky, perhaps, but vulnerable, or beset with problems or dangers – we’re totally caught up. It could be said that every protagonist that walks the pages of a novel is on their personal hero’s journey.

Stories in books have several and varied effects on the reader. Endings might leave them with a feeling of satisfaction, or of vague unquiet...the characters might linger in their minds as they move through their life in the days ahead. But it’s harder for the writer to know if this has happened.

I admit, I still find it difficult to truly work out why some of my own stories are loved more than others. I can mostly put my finger on the reason when it is other people’s work I’m reading, but I sometimes just get too close to my own.

That’s why I love it to bits when readers write to me; either via a card which drops through my door, or an unsolicited email that manages to avoid the junk box, or a message on Facebook or this Blogsite. I always try to respond. Quite recently, I heard from a reader of the Shaman Mysteries who lives in Scandinavia. I was dead chuffed about that – they love their ‘noir’ fiction in that cold place.

At the end of our storytelling workshops, we each had to mount a proper performance. Because the Christmas festivities were upon us, I chose Amahl and the Night Visitors. I remembered this story from my childhood. It was originally a one act opera, first performed in New York on Christmas Eve, 1951. It had a haunting connection with early Christmases for me. Researching it, I found that both the music and the libretto was by Gian Carlo Menottia, who produced a little booklet, revealing how he tried to recapture his own childhood in Italy, where there is no Father Christmas. Instead, as in Spain, they celebrate the Three Kings, who bring gifts, usually at Epiphany. I actually never met the Three Kings—he confesses—it didn't matter how hard my little brother and I tried to keep awake at night to catch a glimpse of the Three Royal Visitors, we would always fall asleep just before they arrived. But I do remember hearing them. I remember the weird cadence of their song in the dark distance; I remember the brittle sound of the camel's hooves crushing the frozen snow; and I remember the mysterious tinkling of their silver bridles.

It was a work of love for me, to recreate an opera into a storytelling performance. As I rehearsed, tears often welled up. But blocking and releasing your own emotion is part of the storytelling experience. For my performance, I didn’t use music or props, just gestures and my words. It was quite terrifying (we’d invited a small audience), but exhilarating, too.

|

Beyond the Border entices you in.

|

Finally, comes the applause. Hearty clapping tells the performer that, not only did they wring the right emotions from their audience, but also that the listeners ‘got’ the story; that the denouement, especially, felt right and fit for purpose. Of course, I got my hearty clap…we all heartily clapped each other. But it made me realise one certain thing about storytelling. Storytellers are very brave people. It is so much easier to put your written story into an attachment and press ‘send’, than stand up in public and weave fictional magic with your own voice.

1

1

Writing before You start Writing

Entering this slower state of thinking allows you to take advantage of the relaxed, twilight world of the trance, where vivid imagery flashes into the mind’s eye and we become receptive to information (as in self-hypnosis) beyond our normal conscious awareness.

Entering this slower state of thinking allows you to take advantage of the relaxed, twilight world of the trance, where vivid imagery flashes into the mind’s eye and we become receptive to information (as in self-hypnosis) beyond our normal conscious awareness.- Daydreaming

- Reverie

- Fantasizing

- Introspection

- Brown study

- Muse descending

- Deep listening

- Slipping into a trance-like state

- Visualization

- Mental pictures

- Head movies

- Relaxed imagining

|

| http://www.mlahanas.de/Greeks/Mythology/Muse.html |

You are now writing directly from your own inspiration. Enjoy!

1

1

The Very Hard Work of Getting Published

The Very Hard Work of Getting Published

The second stage is completion. You’ve now actually got a draft that you’re pleased with. Heck, you might be actually proud of it, and so you should be; getting to this stage deserves huge congratulations from everyone who knows you. (It might also get huge sighs of relief, but that is a premature emotional reaction on their parts.) Believe me, this second stage is hard work. Mentally – you’re glued to a computer while you try, and try again, to formulate a synopsis that will do your novel justice, plus a covering letter that is neither too showy nor too dull. Physically, you need sheer grit and determination to go on when you realise that the synopsis and covering letter needs to be written, with slightly differing nuances, every time you send it out. Emotionally, it’s hard too, when back they bounce. Steadily, you work your way through the Writers and Artist’s Year Book, but no one wants you yet. Then, all at once, some one does want to see the entire book and you realise there may still be typos and other potholes. You need to go through it with a fine tooth comb. When the manuscript returns with a kind of ‘yee-ees…’ you discover that this agent or editor wants heaps more work done.

The second stage is completion. You’ve now actually got a draft that you’re pleased with. Heck, you might be actually proud of it, and so you should be; getting to this stage deserves huge congratulations from everyone who knows you. (It might also get huge sighs of relief, but that is a premature emotional reaction on their parts.) Believe me, this second stage is hard work. Mentally – you’re glued to a computer while you try, and try again, to formulate a synopsis that will do your novel justice, plus a covering letter that is neither too showy nor too dull. Physically, you need sheer grit and determination to go on when you realise that the synopsis and covering letter needs to be written, with slightly differing nuances, every time you send it out. Emotionally, it’s hard too, when back they bounce. Steadily, you work your way through the Writers and Artist’s Year Book, but no one wants you yet. Then, all at once, some one does want to see the entire book and you realise there may still be typos and other potholes. You need to go through it with a fine tooth comb. When the manuscript returns with a kind of ‘yee-ees…’ you discover that this agent or editor wants heaps more work done. - Filled up notebooks

- Had times you didn’t believe in yourself

- Wrote half a novel and dumped it

- Had further times when you didn’t believe in yourself

- Took two years of back-aching, sight-failing keyboard work.

- Almost had to start again anyway.

- And that you’re still working hard to this day.

At that point, you’ll also know, as my friend knows now, just how important it is that people they know buy their new book. That it took a long time to craft it into a readable novel, and that it’s really worth reading, and yet is priced lower than a cinema trip.

At that point, you’ll also know, as my friend knows now, just how important it is that people they know buy their new book. That it took a long time to craft it into a readable novel, and that it’s really worth reading, and yet is priced lower than a cinema trip.

Murder, They Wrote – Three Novelists Writing about Murder

MURDER, THEY WROTE –– THREE NOVELISTS WRITING ABOUT MURDER

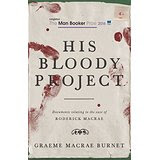

When Graeme Macrea Burnet was interviewed on radio news, he was asked how he felt about being shortlisted for the 2016 Man-Booker with his crime novel.

“It’s not a crime novel,” he replied. “It’s a literary novel about crime.”

I have to confess, as a crime novelist, that did put my back up, a little bit. I don’t believe it’s for writers to announce they’ve created a literary novel…that’s for posterity to decide. In my view, ‘literature’ is something that lasts and grows as it ages…books like Homer’s Odyssey, Orwell's Animal Farm or Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bibles which I blogged about here. But it got me thinking. His Bloody Project (Contraband 2015) cannot yet, in my view, be literature. So is it crime fiction?

The great P D James said that a good crime novel should also be a good novel. All human life is found in the killing of one human by another. So writing about murder surely is always crime fiction! I’m going to look at three recent books that I loved reading to find out if that’s true.

|

Belinda Bauer |

Belinda Bauer doesn’t seem to have any qualms about calling herself a writer of crime fiction. I’ve previously reviewed her work on my blog, and here she is again, with her 6th novel, The Beautiful Dead (Bantam Press 2016). I loved her first book, Badlands, but I did feel the end was a bit weak, a bit unbelievable. This time, no worries about that! I loved the way Bauer took a ‘smoking gun’ in the form of a pair of handcuffs, which the main protagonist, TV crime reporter Eve Singer, has become obsessed with as she’s tracked and taunted by a serial killer she’s featuring on her news items. I expected them to be used in some way to secure her life when it was eventually under intense threat, as I knew it would be! But when those handcuffs were put to use on pg 319 of the book, I stood from my seat and crowed in joy. What a twist! What a perfect ploy! A great, twisting surprise is essential in a crime novel. But Bauer also delivers elegant description, strong metaphor and deep investigation of the human condition. She examines what being a killer is – how close each of use could get to murder. A crime novel? Decidedly, but great, contemporary fiction, too.

Helen Dunmore is known for her lyrical poetry and her award-winning fiction, including the best-selling The Siege, which is set during the Nazis' 1941 winter siege on Leningrad So I wasn’t surprised to find that in her most recent book she turned her hand to a cold war thriller, set in England in the early 1960’s. In Exposure Penguin, 2016) Although she uses three points of view…the hardened old double agent, the fresh, young candidate pushing a pen in the office of MI6, and his wife, mother of two young children, a typical stay-at-home mum, but a woman with a sharp mind. The shock of the killing towards the end of the book demonstrated for me that one of our most outstanding writers (Good Housekeeping review) can

‘do’ murder and do it well, focusing on the victims, both of the spying industry, and of the machinations of corrupt individuals. Is this literary fiction? Or a spy thriller? I can’t honestly see why it can’t be both.

‘do’ murder and do it well, focusing on the victims, both of the spying industry, and of the machinations of corrupt individuals. Is this literary fiction? Or a spy thriller? I can’t honestly see why it can’t be both.

Graeme Macrae Burnet’s His Bloody Project didn’t win the Booker in the end. But Burnet’s book is the one that I enjoyed the most from the shortlist. I enjoyed it so much, that I now have a little more sympathy with his comment about literary fiction.

His novel is centred around a vicious triple murder – a man, his teenaged daughter and his baby son – by an angry young boy who lived in the same crofting community in 19th Century northwest Scotland. Burnet uses several point-of-views to create the novel, starting with the gripping account by Roderick Macrea as he languishes in jail, waiting for his trial to begin. This account is the gruelling and bitter story of his short life as a crofter. Although he shows promise at school, he leaves early to start working with his widowed father, who is perhaps a bit lacking in the smarts department, unlike his son. Life is backbreaking, crushing. And the powers who own the land turn a cold, heartless face away from the punishing routine that puts meagre food in the crofter’s mouths. Very soon, as the story is related, it becomes clear why Roddy kills. He is drawn to do so, from the moment he has to batter an injured sheep to a humane death. The second half of the book are accounts from the defence lawyer and the early 19th psychologist he has called in, and from newspaper articles about the trial.

I could not put this book down. Firstly, I needed to know why and how the murders happened. Lastly, I needed to know if his kindly lawyer managed to secure Roddy clemency from the gallows.

Is His Bloody Project a piece of crime fiction, Mr Burnet? I would say so. A piece beautifully written, and a deeply investigated book which looks into the nature of murder. It's also a book that may stay loved over generations and thence become ‘literature’, but at the moment, it’s crime fiction.

A romping good read, but also, like Bauer’s and Dunmore’s latest fictions, it’s about murder. They’ve all written about the deadliest of crimes, and I cannot see what is wrong with admitting that they’ve ended up with great stories that are crime fiction.

1

1

Seven Amazing Books Only I can Recall

Instead of reviewing books on the best seller list, or books winning prizes, I’m looking at seven books that have generally been forgotten.

It is 1855 and Erasmus Wells, an introspective naturalist, wants to extend his scholarship on this expedition to the Arctic captained by his brother-in-law-to-be, Zechariah Voorhies. Zechariah is nothing like shy Erasmus. He’s an impetuous smart-aleck who hopes to find a legendary ‘open polar sea’ and a missing explorer who disappeared a decade before.

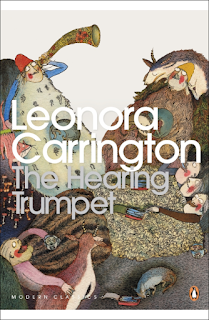

It is 1855 and Erasmus Wells, an introspective naturalist, wants to extend his scholarship on this expedition to the Arctic captained by his brother-in-law-to-be, Zechariah Voorhies. Zechariah is nothing like shy Erasmus. He’s an impetuous smart-aleck who hopes to find a legendary ‘open polar sea’ and a missing explorer who disappeared a decade before. Talking of the surreal, I was listening to A Good Read, the longstanding programme on reading and books on BBC Radio Four, when I first heard about The Hearing Trumpet. “This is a bonkers book,” said one of the programme’s guests, who’d been asked to read it. “It’s mad. Utterly bats in the belfry.”

Talking of the surreal, I was listening to A Good Read, the longstanding programme on reading and books on BBC Radio Four, when I first heard about The Hearing Trumpet. “This is a bonkers book,” said one of the programme’s guests, who’d been asked to read it. “It’s mad. Utterly bats in the belfry.” I still have my battered copy of Cry, the Beloved Country by Alan Paton, possibly the most important novel to come out of South Africa before it abolished apartheid. It was published in 1948 the US; in South Africa it created much controversy. When I opened it again to write this, the smell of old books came wafting out, taking me back to the seventies, when I bought it at a second-hand stall. At that time, South Africa apartheid was still universal, with vicious race laws. Nelson Mandela was incarcerated on Robin Island and, here in the UK, I wanted to find something that would explain all of this to me. Cry, the Beloved Country, with its major theme of the overwhelming problem of racial inequality, suited my needs. It’s still an incredible read, and a reminder of how important it is not to turn back the clock.

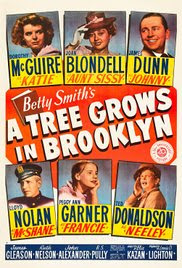

I still have my battered copy of Cry, the Beloved Country by Alan Paton, possibly the most important novel to come out of South Africa before it abolished apartheid. It was published in 1948 the US; in South Africa it created much controversy. When I opened it again to write this, the smell of old books came wafting out, taking me back to the seventies, when I bought it at a second-hand stall. At that time, South Africa apartheid was still universal, with vicious race laws. Nelson Mandela was incarcerated on Robin Island and, here in the UK, I wanted to find something that would explain all of this to me. Cry, the Beloved Country, with its major theme of the overwhelming problem of racial inequality, suited my needs. It’s still an incredible read, and a reminder of how important it is not to turn back the clock. One rainy afternoon, I watched the 1945 black and white film A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, on the TV. I was a young mum at the time, and was drawn to the story of this impoverished but aspirational second-generation Irish-American living in Brooklyn, New York City, during the first two decades of the 20th century. So I did what eleven year old Francie Nolan did all the time; visit my local library to borrow the book. Written in 1943 by Betty Smith, the book was an immense success at the time. It must have hit the same nerve with that reading public as the film, and subsequently the novel, did with me. It’s the story of family life, and the immigrant experience. The Nolans are poor, often hungry, but they fill their home with warmth and love. The main metaphor of the book is the Chinese ‘Tree of Heaven’, which grows outside the window of the family’s run-down tenement building; a symbol of Francie’s desire for a good education, which she manages to obtain through some subterfuge with the US school system. This beautifully written account of the American immigrant experience might be due for a revival, for various reasons, right at this moment.

One rainy afternoon, I watched the 1945 black and white film A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, on the TV. I was a young mum at the time, and was drawn to the story of this impoverished but aspirational second-generation Irish-American living in Brooklyn, New York City, during the first two decades of the 20th century. So I did what eleven year old Francie Nolan did all the time; visit my local library to borrow the book. Written in 1943 by Betty Smith, the book was an immense success at the time. It must have hit the same nerve with that reading public as the film, and subsequently the novel, did with me. It’s the story of family life, and the immigrant experience. The Nolans are poor, often hungry, but they fill their home with warmth and love. The main metaphor of the book is the Chinese ‘Tree of Heaven’, which grows outside the window of the family’s run-down tenement building; a symbol of Francie’s desire for a good education, which she manages to obtain through some subterfuge with the US school system. This beautifully written account of the American immigrant experience might be due for a revival, for various reasons, right at this moment.  |

| Image from the 2010 London dramatization |

Perhaps you have read some of these long-forgotten books yourselves and loved them as much as I did, or maybe you hated them with equal passion.

Perhaps you have read some of these long-forgotten books yourselves and loved them as much as I did, or maybe you hated them with equal passion.

1

1

1

1